The murder of María Soledad Morales in the province of Catamarca

VER VIDEO

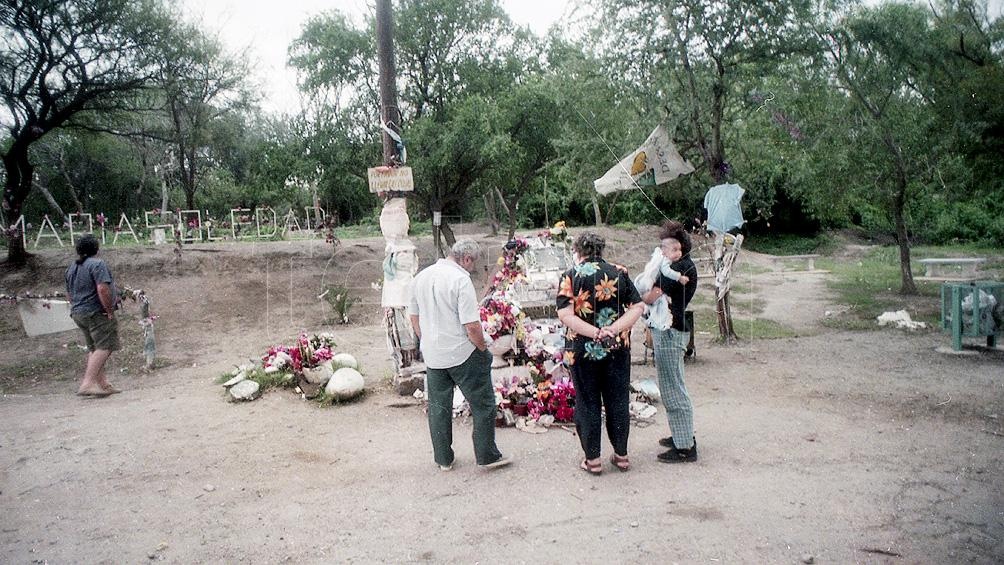

Catamarca, September 7, 1990. A 17-year-old girl goes out dancing and meets her boyfriend, but never returns home. Three days later she is found brutally murdered on the outskirts of the provincial capital, with indications that her body had been subjected to all kinds of abuse.

The case shocked the country: María Soledad Morales was 17 years old, went to a convent school, and was seen smiling and surrounded by friends. From the beginning, the speed with which they sought to prove a supposed hypothesis and close the investigation was notorious.

Photo: File

Photo: File

The police chief himself, Miguel Ángel Ferreyra, ordered the body to be washed, thus eliminating essential evidence. Later, among many other shocking discoveries, it would be revealed that he was the father of one of the killers.

It was precisely these irregularities that gave rise to suspicion: the provincial power was involved and protecting the perpetrators of the murder. “The children of power” began to call them. His media appearances denoted absolute impunity.

Faced with this, the entire province began to mobilize in the so-called “Silent Marches.” The first was in Catamarca on September 14, 1990, but they quickly spread throughout the country.

Photo: File

Photo: File

The complaints repeated that they saw María Soledad leave a nightclub drugged and that she was put in a car with several men. The word “party” was the common denominator of all the chronicles.

However, the social demand did not revolve so much around the crime as a case of gender violence, but focused more on the word ‘corruption’ and, above all, the feudal power that seemed to run the province.

Among the names of the assassins were Guillermo Luque (son of a national deputy) and Pablo and Diego Jalil (nephews of the mayor).

Everything that surrounded the case was a scandal and, in this context, a large part of the Catamarca police staff were retired.

Photo: File

Photo: File

Luis Patti, a repressor during the last military dictatorship, was sent from Buenos Aires to investigate the case, but his complicity with the Catamarca apparatus was treacherous from the outset.

The case was so paradigmatic that the film came out in 1993, directed by Héctor Olivera and starring Valentina Bassi. Since the crime was not solved and the trial had not even started, the names of the perpetrators were changed.

Finally, the only prisoners were Luis Tula and Guillermo Luque. Today both are free.

The case, however, shaped the visibility of this type of crime, where the victim is a woman, although its most important mark is that of a society breaking the silence to challenge power.