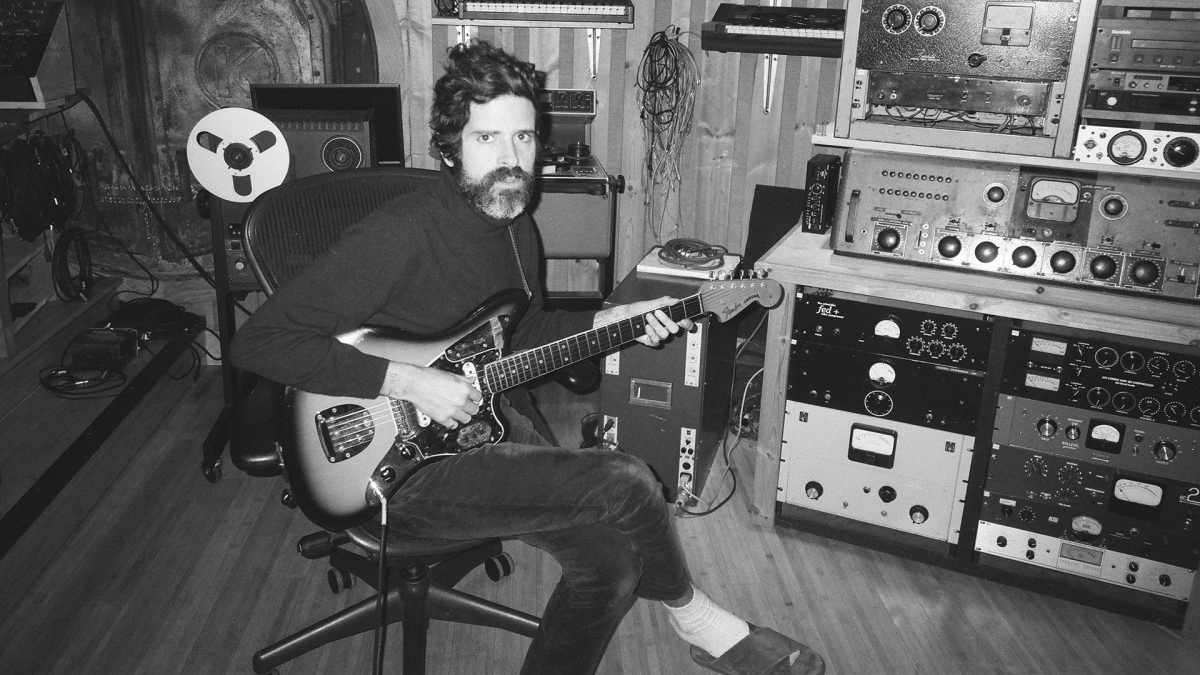

Devendra Banhart: “The album was about time, how the world changed.”

Devendra Banhart: “The album was about time, how the world changed.”

Before his arrival in Buenos Aires to be one of the main attractions of the Music Wins Festival, the Venezuelan-American musician Devendra Banhart spoke with Télam about his musical current affairs, the reunion with the public and a new approach that he found in the composition that increasingly dispenses with words in an attempt to “musically and poetically interpret how fear and pain are processed”. .

Banhart, who will give a first performance tomorrow with his band at the C Art Media Complex in the Chacarita neighborhood of Buenos Aires, to celebrate the arrival of the festival that on Saturday will occupy the Club Ciudad de Buenos Aires, bringing together international and local names such as Metronomy, Chet Faker, The Blaze, The Magnetic Fields and Zoe Gotusso.

“The new record is trying to interpret musically and poetically how fear and pain are processed,” says Banhart.

“The new record is trying to interpret musically and poetically how fear and pain are processed,” says Banhart.

“We are going to be like cockroaches, we are going to be everywhere. We really want to play and discover the different groups at the festival. I know a lot of Argentine music from the sixties, seventies and eighties, but not so much what is happening today In the group there are three of the guys who have never been to Argentina and who want to discover everything”said the musician.

“The new album is trying to interpret musically and poetically how fear and pain are processed. Knowing that this happens a lot to me, that if it is not processed in a healthy way, fear and pain turn into depression and repression .”Devendra Banhart

With a long discography based on folk, in its various aspects and in his encounter with Latin music -especially with Brazilian ‘tropicalism’-, the musician and visual artist born in Texas but raised in Caracas established himself as one of the most interesting and praised troubadours of this century.

-Lately you have been on stages in the United States, Mexico and Japan. How has your reunion with the public been turning out?

-It was little by little: I want to live in the sea and breathe under the water, but right now it’s putting a little finger in the sea, then another. I played in Mexico but I did it alone, without the band, and in Japan I went on stage three times with two friends. There’s a lot of excitement connected to this trip, because it’s going to be the first one we’ll do as a band since the pandemic. It will be the first time that we can share, explore and spend a moment together. Furthermore, we are in love with Argentina, Chile, Ecuador and Venezuela, and delighted because, in addition to playing songs from all the albums, we are going to make three new ones. We just finished the record a week ago.

-You once said that, when it comes to composing, you always start with the lyrics and that the music appears only later to occupy the rest of the spaces. Why did you immerse yourself in the ‘ambient’ instrumental music in “Refuge”? Did it appear as a response to the lack of being able to narrate and observe others?

That’s a better answer than I could give. At least for me, it’s not that there were no words, but we did make an album inspired by all that music that was helping us in the darkest moments of the pandemic. When you couldn’t leave the house, I would listen to Alice Coltrane, Harol Budd and Don Slepian. Music that is part of my being. With Noah (Georgeson) we were very inspired by all that “new age” music we listened to in our childhoods: he grew up in a very hippie town in northern California with his parents meditating, just like mine did in Caracas. It’s music that leads you to be able to sit down, calm down a little bit. Something we needed and felt a lot. There aren’t many lyrics on this new album that we just finished either. It is true that for me everything begins with the lyrics, but there was so much that had happened in these years, so many emotions and so much to write, that I would end up with 10,000 lyrics for a single song. I preferred to say as much as possible with the least, I went in that direction.

-And those few words provide a look at the return of social gatherings?

DV: Well, for me at least, the new album is trying to interpret musically and poetically how fear and pain are processed. Knowing that this happens to me a lot, that if it is not processed in a healthy way, fear and pain turn into depression and repression. Because pain will never come, it will always be there, but if one knows how to process it in a healthy way, it can turn into courage and compassion, but if it is not processed well, it ends up as depression. It’s like being emotionally constipated (laughs). The album was about time, about how the world changed. And it scares me when it doesn’t change, it’s a paradox when we want “everything to go back as it was” and at the same time “everything changes”. Today at the shows we all hug each other again and it feels like nothing has changed, but at the same time everything has changed. It’s very interesting: everyone knows what’s next but at the same time not. It’s a paradox because I want things to be normal, whatever that means, and I also want things to be completely different. That will never happen; only I can change. The world never changes, only you change.

-Is it true that in the pandemic you also changed your way of painting? And at what point do the musician and the visual artist dialogue? Can they coexist at the same time?

-I started writing songs at the same time I was painting. I went to San Francisco College of the Arts, an interdisciplinary college. I ended up doing music in this career, but I was always painting. I have never had time to paint in oil because it is very difficult and requires a lot of time that I never had. I was only just getting started, finally, in the pandemic. I composed these “lockdown faces” as portraits and reflections of all these conversations I had with different people. In all of them, I saw fear, anxiety, terror, mania, hysteria. They were very natural drawings, which I was drawing while talking with them. I think my paintings are fatal and horrible, but I paint, whether it’s a giant penis or whatever, until I laugh. It’s a very childish thing: I go where nobody goes, I see someone’s face crying and I start laughing. This amuses me. Writing songs doesn’t amuse me because it’s a much more intense thing. A song about a friend who has just died is much stronger, while painting is a moment to enjoy a joke.

-And that is why it is important for you to walk that path together with “mentors” or “guides”, as you once said?

-For me it is very natural to look for mentors and guides. I think we don’t have many good guides. You have to be very careful with the guides and mentors you choose. It is a very magical, mysterious, natural and intuitive process. Maybe I like how they walk, how they talk, the art they make. I start because I love their art, but also because they can shape our way of being, something that is almost sacred. At the same time, you just have to be totally smart with your intuition because it’s like a dance; You don’t have to be totally open to anyone and you don’t have to be closed to anyone either. It is a very delicate dance, but when it is done in a disciplined way, with a thirst for honesty, your mentor and your guide can find you too. It is very interesting, it is like a signal that it sends you.