Sebastiani: “We have a culture of gestating, but we do not have a culture of dying” / Photo Julián Álvarez

Sebastiani: “We have a culture of gestating, but we do not have a culture of dying” / Photo Julián Álvarez

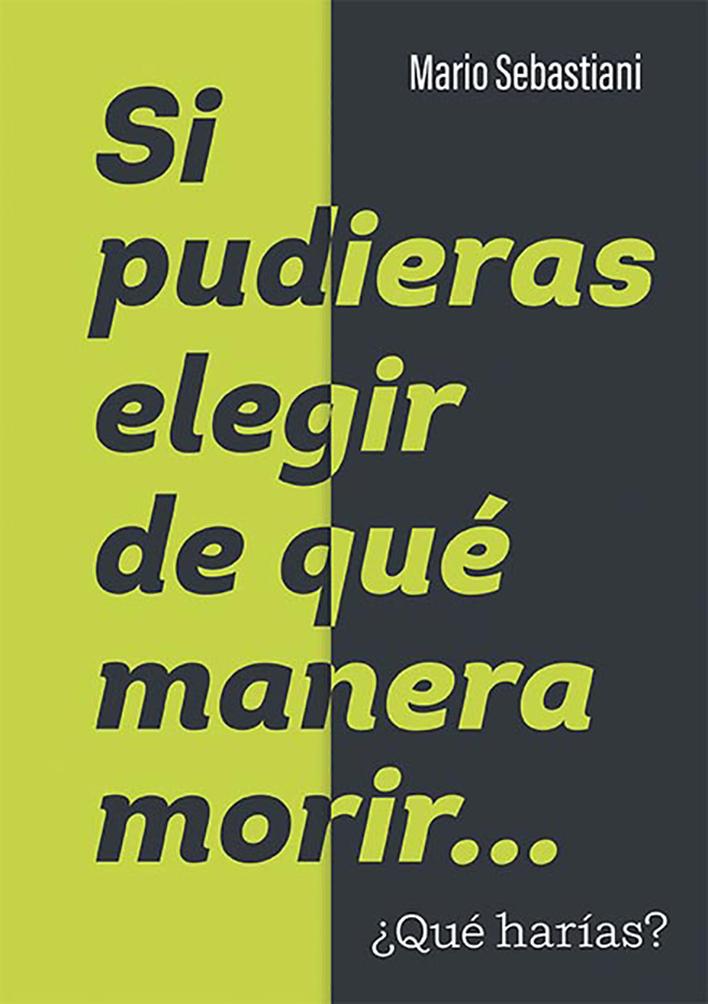

“If you could choose how to die, what would you do?” is the main question that runs through the new book by Mario Sebastiani (1951), a doctor and historical militant for the right to abortion, who in this work recovers the central arguments in around the need for a euthanasia law that enables legal death for terminally ill people, but also for those who no longer want to live in pain: “We have a culture of gestating, but we do not have a culture of dying,” he told Télam.

On various occasions and in different contexts, Mario Sebastiani asked different people how they would like to die. The answers were always similar: sleeping, during a nap, suddenly, almost without knowing it. Instead, he maintains that he would prefer to die surrounded by his people, with dignity and without pain. He would like to know when, so that he can drink the best wines from him before. He wants to die without suffering and if his state of health requires it, medical assistance.

Nowadays In Argentina, six bills are being worked on to legalize Medically Assisted Death (MMA), a framework that today exists in the Netherlands, Belgium, Colombia, Canada, Spain and New Zealand. Sebastiani emphasizes over and over again the need for personal freedom both to gestate and to die. “We cannot choose when to be born, but we can choose how and when to die”he tells Télam, although he points out that ours is a culture in which death is not talked about, much less is it naturalized.

In the book “If you could choose how to die, what would you do?”, from the El Ateneo label, the author recovers the emblematic cases in the world that opened the debate for an MMA Law in other countries, opens the game, crosses the arguments medical, civic, ethical and philosophical and builds the idea of the body as a territory of political dispute.

– At the beginning of this book you say that you write as a citizen. However, then it is strongly crossed by your character as a doctor and has a great philosophical component. How does all of that balance?

– This book is first written as a citizen because it has a foundation: I want a law. The book is part of that militancy, having a law. Why? Because I am a citizen. I as a doctor could access someone to help me die, but I want them to help anyone who wants it. That it be a legal event, that we all have the same right. The medical deformation is because this is called Medically Assisted Death (MMA), therefore, medicine has to intervene. Medicine is going to tell us how much time we have left, what that path will be like, and also drugs are managed by medicine. In Spain, for example, people who choose to die do not die in the hospital: euthanasias are resolved at home. In Switzerland, at the Dignitas Clinic, assisted suicides are carried out. It is very necessary to de-dramatize this situation.

– Today we can talk openly about the desire to be a mother or not, about the possibility of an abortion in the face of an unwanted pregnancy. And of desire on a lot of other issues. Why do we still live in a society where the wish to die is taboo? Why is life still a duty and not a right?

– It’s our culture. We have a culture of gestating, but we do not have a culture of dying. We don’t like to talk about death. I like to talk and you don’t like it, it seems to me. Death should be a talk at the next barbecue, at the next intimate situation with someone. For Orientals, death is a much better place. We are disenchanted. The desire to gestate is well seen, it is a Marian desire, from the Virgin Mary, who is not stained by sex. Under this idea, every baby is good, no matter if you wanted it or not. There is an important fact: 10 years ago there were 760,000 deliveries per year, today there are 533,000. The attitude is to reward gestation: bring life. But we do not have an attitude towards participating in one’s own death. If I want to participate in my end of life, it is questioned: how do you want to participate? And yes, I want to intervene, I want to say what I want and what I don’t. We cannot decide how or when to be born, but we can decide about death.

– In a section of the book you say that “lying is power”, while the truth is a moral obligation. How can we deepen this point, linking this idea with the possibility of voluntary death?

– In Argentina, doctors dramatize telling a patient that he is going to die. And there it begins with the power of lies. I think you’re an asshole if you don’t tell the patient that he’s going to die. If a person goes to the United States, given any diagnosis, they will be told how much time they have left to live, with precision and rigidity. We see that in the movies and we say: “what a cold, hostile medicine.” How cold? They are telling you the truth. We suffer when we see that. We have the white lie very accepted, we see it clearly in politics. And we have a passive attitude.

– The general approach of the book is euthanasia as individual freedom, and this is connected with the fight for individual freedom in access to legal abortion. Why do you think human beings still have to “fight” to be free?

– I am not specifically interested in abortion or euthanasia, I am interested in freedom. These are two things that I have to be able to receive and I don’t want a legislative majority to handle it for me. I don’t want the state to handle it. And personally, I don’t want my family, my children or friends to decide. What eroticizes me is freedom. In the abortion we had a conflict: “the two lives”. There is no conflict here. For someone to be able to choose euthanasia or assisted suicide, they have to be autonomous and they have to be competent. Another does not kill you because he wants to, he kills you because the person in question wants it. It is at the request of the patient. Given the questions about the situations of patients who are in a coma, I say that the advance directive is important. Talk about death, tell the family what we want and what we don’t. Ideally, leave it written. Respect. Not lie. Don’t underestimate who you choose and ask for that. They are struggles to be free, they are militants for freedom, but for that you have to become aware. Whose is your life? If you leave it to the doctors, you’re going to die when the balls are sung to them. If you leave it to your family, they will have to agree among themselves. Life is for one.

– The book recovers this idea that people in the West, especially agnostics, cannot talk about death, we are afraid of it. We have a structure that makes us think that death “is the worst” and life “is the best.” How could these beliefs be disarmed?

– Listening to people who ask to die because they feel that death is the help or the solution to their problem. Today we normally die in pain, with suffering or indignity. What ability do others have to measure my pain? Spiritual pain, suffering. We can see it clearly in the movie “The Sea Inside”. Dignity is not measured, each one has its own intrinsic dignity. When people begin to suffer in their own flesh a situation like this with a mother, a father, a friend, that’s when this much-needed thing begins to happen little by little. A social and cultural construction grows where we have to talk about death.

-There is in the book an in-depth study of the role of medicine, which today serves us to prevent diseases, to cure them or alleviate suffering. But you suggest that it should help us die, too. Is a country possible where we can have this type of medicine, at the service of life, but also at the disposal of death?

– The postulates of medicine are to prevent diseases, cure them and alleviate suffering. But there are people who refuse. Some cite the Hippocratic oath, but that was 2,600 years ago! Societies change… And also in ancient Greece and Rome there were judges who had potions to kill people. Euthanasia has always existed, it helps her die. Because we became intolerant of each other’s suffering. People don’t want to see other people suffer; The case of mercy killing in wars. In the Netherlands, in 2003, a doctor killed her mother and went to court. The woman was imprisoned for 5 minutes and then she understood that the intervened death had a reason for being. And so they put the issue on the table and then the law came out. It is essential to modify the culture of death and understand that helping to die is very important.

– You say at one point that the body belongs to the State, the body as a place where cultural battles are fought and the patient as a person who does not intervene in these debates. What is reality like today and what horizon, in legislative terms, do we have?

– Life is our legal right, but we have to assert it. In fact, anyone can commit suicide if they want to. Life does not belong to the State, medicine is what appropriates life. The legal right is mine. And I do what I want. If this parliament does not modify the law, if someone helps another person to die, they go to jail. If I have a patient who is screwed up and I help him to die because the guy asks me to, and I help him because it is a moral attitude, I go to jail. And the doctor who doesn’t help him, and enables the pain, has no problem with the law. We cannot continue with this distortion of reality, because it is also a lottery who wins you at that moment. Someone who helps you or someone who holds your pain. Today we have six bills, I believe that next year it will come out. We are close. Because I am optimistic, because I am breaking my soul to get it out and because I do not see great hostilities.